Beautiful Attachment

how loving where you live is about way more than just a feeling

I’ve been reading This Is Where You Belong: The Art and Science of Loving the Place You Live. by Melody Warnick, who moved to five different states in just fourteen years. She writes about place attachment, something she says is less a feeling than it is the end result of particular behaviors, many of them fairly predictable - subscribe to a local newspaper, find local events online, join a club (book, running, etc).

Chief among them is getting to know your neighbors in a personal way. She cites studies that support the benefit of neighborliness: people who know their neighbors’ names and trust them are 67% less likely to have a heart attack, and 48% less likely to have a stroke.

I’m glad I didn’t read this book during our first weeks here - I would have felt despondent that we’d never feel attached to our new home. My first experience in the Lisbon airport was such an unmitigated disaster, the h and I both wondered, is Portugal rejecting us? In the first ten days occupying the place we bought in Belas - a village halfway between Lisbon and Sintra and whose name translates to “Beautiful”- we were robbed twice. One robbery was a home invasion, and I woke up during its commission. We called the police and they didn’t speak English and hung up. So we called the AirBnB host from our previous visit, and she called the police for us. Three officers showed up; one spoke English, and the h offered him the only chair in the house as he asked questions and filled out his report while his colleagues studied me and our surroundings.

We were staying in the big house on the property, a palaceta we have nicknamed Brokedown Palace for reasons that are obvious when you are in it. It was not in great shape, no plumbing or electricity and with forty years of accumulated dust, but it was in better shape than the other houses one of which had no roof and the other which had no windows and in some rooms no ceiling or floor.

The entryway to Brokedown Palace opens onto the front porch with a pair of floor to ceiling double doors that feature four large windows with locking shutters - only at the time of the robbery the window glass had fallen out of the rotting frames, and the locking shutters didn’t lock, thus enabling easy access for Senhor Ladrao.

Each wall of the ten foot diameter room features a set of double doors overtopped with a glass transom. The doors and doorframes were stained with ancient fingerprints and yellowed with nicotine; the glass transoms were opaque with dust and spiderwebs. The tile floor gritted underfoot; though I swept regularly, little pieces of wall and ceiling dropped constantly to the floor; any touch to the concrete where long-ago thieves had chipped the tiles from the walls resulted in a cascade of dust, an admixutre of dirt and crumbled concrete.

The police officers tried not to stare too hard at the state of things but you could just see them wondering, Why in the world would anyone live in such a place?

Back then we propped the doors and windows open during the daytime for a breeze and to air out a house that had not been breathed in for decades - the constant breeze ensured the dust and dirt were replaced almost as soon as I swept it each morning and evening.

It was a hard start to our stay here. I belong to a Facebook page for people moving to Portugal, and while it is generally filled with people at great pains to be helpful to one another, when I posted that we were robbed, I received a dismaying number of comments suggesting that we brought it on ourselves. Others criticized me for being too passive; in true American fashion one woman remarked how if SHE had been robbed she would pursue the thieves and punish them roundly. When I explained my husband was in fact at the door of the thief in that moment (courtesy of AirTags in the stolen backpack) and pounding on it with a metal bar, she reversed course and said he should be more cautious than that.

Just typing this, I have a full body recall of my anger and helplessness; here I was in a new country, experiencing disaster after disaster and wondering if I’d just made the biggest mistake of my life, and the country I still thought of as home could only offer criticisms and worthless advice. I felt rejected and dejected in equal measure, unmoored, a person who no longer had a place to call home.

Certainly the Brokedown Palace we had just taken occupancy of was not yet a home - it was still filled with the detritus of the previous owners. And excepting our clothes, the only things we’d brought with us had just been stolen. Going back to the US would be no simple matter - we were more than halfway through many of the processes tying us to our new country, and unwinding them would take many months. Not to mention we no longer had a home to go back to, unless you count the homes of our moms. I’m sure they both would have welcomed us for a short stay while we figured things out, but it wouldn’t have been home, just a place to stay with any comfort provided equally balanced by the knowledge of the inconvenience our presence represented.

Neither of us wanted to go home just because of a few ugly hiccups; we knew what we’d signed up for, and that coming here was a long term proposition, not a lark. So we set about making it our home. A lot of hard, dirty physical labor built a growing feeling of ownership. When you prune trees and chop a mile of ivy off walls and fences; when you wrestle dirty sopping mattresses out of buildings and down sets of steps, around corners and into a truck; when day after hot day you drag huge piles of branches and bracken across a field to stuff into a burn barrel; when you fill buckets with water, soap, and bleach and, wearing rubber gloves that reach to the elbow, scrub every square inch of ancient dirt and tobacco stains off the walls a magic alchemy happens, and a place starts to become yours.

I’ve lived in a lot of different places, as has the h. I started in the midwest. in a small town in southern Illinois (whose name, Belleville, also translates to beautiful). From there I jumped to Indiana for grad school before advancing steadily west, courtesy of employers, from Missouri to Texas to California. I’ve had at least eighteen addresses since leaving college. Now, I have two - Alaska, where we retain an American footprint as we build a life here, in Portugal.

I regret to say that I did not bond too much with any of these places I have lived; my life revolved around the work that brought me to each city, and while I did things like run, play in softball leagues, go out to dinner etc. my ties to each place tended to be based on ties to the job - even my friends were provided by the job. The only exception was San Francisco, a city I did not move to for work, but chose to live. It was difficult there, too, at first - I had no built-in community of friends from work to do things with, no job to go to every morning. I was launching my writing career, and it forced me to go out and investigate what the city had to offer. At the age of 40, I had to learn how to make friends and learn how to navigate a large city for the first time in my life. And I did, though I admit the first places I habituated were Blockbuster and bookstores - places you go to get things so you can go home and be alone being entertained by those things.

Eventually I found my people and my places; I also found my h. I made a few close friends in Austin that I remain friends with; I miss them, though I don’t particularly miss that city. But San Francisco will always have part of my heart; I had, and still have, place attachment to my city by the bay.

When I moved to Portugal I expected it to be permanent, and not only because it reminded me of an Old World San Francisco. There are many things I love about the country - the culture, the food, the people, the music, and the landscape, for starters. But I didn’t know all of that, not really, when I got here. All I knew was this property, which we inexplicably fell in love with, and about which I had the very specific thought/intention that this would be my final home in every sense.

When we first entered the house, fumbling with the delightfully archaic looking key, it was a sunny late morning but pitch dark inside; these locking wooden shutters are an old but very effective technology for blocking out light and heat. The h had a headlamp with him, as he always does (also: a knife, a bike tool, a portable coffee press and bean grinder, hand sanitizer, mosquito netting, a lighter, and dental floss). He strapped it on and located the shutters in each room of the downstairs - breakfast room, double living room, dining room (while carefully avoiding gaping holes in the floors) and pried them open. Rust and paint chips rained down with each opening; in some cases the window glass simply fell from the frame to shatter at our feet or outside in the courtyard.

The h went upstairs, guided by his single spear of light, opening the shutters in the rooms as he went, the house quickly swallowing the sound of his footsteps as he reached the third floor.

I remember standing in the hallway of the first floor, which was still dark - the hallway and the kitchen have no windows, just doors at the end, which were barred shut - listening to the silence (one of my favorite Portuguese words: silenciosamente) of the house.

Hello, I called to whatever might be listening. We came a long way to be here. We’re going to make this place a home again.

I am a horror writer, and maybe more alert to things that go bump and slither than the average person. But there was no scurrying of rodents or spectral energy; the house was quiet with the weight of decades. With all the shutters opened and air flowing through, it seemed to sigh around us.

A side note on ghosts: Almost everyone who has been here at night asks if we’ve seen/heard/sensed them. The lack of electricity in the Brokedown Palace makes everything shadowy and somehow secret at night; the holes in the ceiling and floor yawn darkly, the remnants of wallpaper clinging to the walls stir now and then with an itinerant breeze. All of this puts people in the mind of spooky stuff. The h swears he has heard a woman’s voice a few different times; I think it was a hen outside, they sound weirdly human sometimes. A visitor said she heard footsteps on the stairs a few times. And once, while standing alone in the quinta, crying quietly over missing my daddy, I felt a hand touch my back.

But in general the only thing that haunts this place is neglect, and the only place that feels like it might have some sort of spiritual essence is not the dank dark concrete bunker-like cellar right out of a Edgar Allen Poe story, but the enormous spreading fig tree that grows on a hillside ascending from the pool. It is awesome to behold, producing figs twice a year. If ever there was a place to hold a seance, it is under the great reaching, enclosing branches of that tree.

All of that was a bit more than a year ago; today, it is part of my morning ritual to unlock and open the shutters (all of them now cleaned with latches that open smoothly) and let the morning light stream in through the new glass panes. We have not yet replaced the windows, but the h, with the help of neighbor Alberto, re-glazed all the broken and missing panes. Precisas janelas atras o inverno, Alberto scolded, clearly worried. It will be cold, the rain will come in,

He not only gave us panes of glass, but measured and then cut them to size in his workshop, then inspected the h’s installation, grunting his approval. The window frames themselves have gaps that allow wind to whistle right into the house, but closing the shutters kept out most of the wind and rain of winter and spring, and now we have considerably fewer insects flying in.

Another suggestion Warnick makes to feel attached to your new home is to lean on super connectors; we haven’t really located those yet, but interestingly I have sort of become one: early on we met Ana and Jonas from across the street, and though Alberto just two properties down they had never met one another until we made the introductions. The other day, heading up the cottage steps, I noticed Alberto across the street chatting with Ana. Judging by Alberto’s gestures toward our place, he was filling her in on the improvements that were visible from where they stood - the raised garden beds, the greenhouse, the newly planted fruit orchard. They both waved when they saw me looking over; I waved back.

We’ve also introduced Alberto to our workers; a few days ago when Alberto brought us a bag of lemons I noticed he’d also left a bag for Tiago to take home.

In addition to the people we’ve met, we have places we’ve become regulars at: the cafe at the grocery store, where we ate daily for our first six weeks in country for a mostly practical reason: the cafe had a power outlet that enabled us to plug in all of our devices and charge them up for the day as we ate breakfast and one of us did the daily shopping. Over time the cafe workers grew to know us; sometimes they’d see us walking past the windows on our way in, and our order would be ready for us when we arrived at the counter.

Another thread in our braid of place attachment: the churrasqueria down the street, run by Carlos and Elaina. Every time we have a visitor we take them down to the churrasqueria for some barbeque; in return, they have introduced me to their daughter and granddaughter when they stop by the shop.

Another thread is the butcher shop next door to the churrasqueria. I do not yet know the name of the man and his wife who run the shop but nevertheless we exchange bom dias and a few words every day because Jake has adopted them as true Jakebrothers. The butcher gets such a kick out of Jake greeting him each day. Once, he was walking in front of us, on his way to Cafe Largo up the street for some pequeno almoco (the word for breakfast is literally “little lunch”); Jake kept trotting faster and faster ahead of me, straining at the leash. I was getting irritated, not having recognized the butcher from behind, but Jake’s nose knows, and he put it (his nose) right into the butcher’s hand. The butcher whirled, startled, and burst into such a loud laugh that everyone on the street turned to look. Jake was quite pleased with himself.

We make regular appearances at two local restaurants - Cotorinho and Santidunica - as well as four local bakeries: Casa Mae, Cafe Key Largo, FoFo de Belas, and Delícia de Belas. There are two mini-marts that we frequent - Rampinho and Supermercado de Belas. In each of these places the owners and workers have come to recognize us, even waving and calling “tudo bem!” when they see us about town.

Every day I walk with Jake through the village park aka the Jardim 25 de Abril (the date of the Carnation Revolution that brought democracy to Portugal in the 1970s). This is where I met Margarita, an elegant older woman, perhaps in her late 70s, who walks with a cane, is always well dressed in a pantsuit or jacket and slacks, and when the weather is fair can be reliably found sitting on the bench at the eastern-most point of the park. She speaks no English, but I have gleaned from my rudimentary Portuguese that she lives in one of the lovely apartments with the 16-paned windows behind the park, abutting the Queen’s land. She talks a mile a minute and I mostly nod and smile to hide my panic and catch about twenty percent of it. Beleza, she always says to/about Jake.

Another source of attachment is our garden. There is nothing like growing your own food and flowers to make you feel proprietary about a place. Cutting the weeds down has a similar effect.

The h’s sources of attachment are mostly the same but he has his own, namely tools. The other day he came home from picking up a chainsaw. I was busy working but suddenly heard a bunch of low baritone voices go “Oh whoa ho ohhhhh uau (which comes out as “wow”)” and knew without even looking out the window the h had arrived home and was showing the workers his new acquisition. Today, Alberto came over with his twice weekly delivery of fresh bread, plus some mint to transplant, and a chrysanthemum in a clay pot courtesy of his wife Rosa, who has also gifted us with six orchids.

Ah! he said, espying the new chainsaw. Muito bem!

Sim, the h said. Profissional qualidade.

There followed the kind of conversation only men have and care about and you’ll just have to trust me because I didn’t listen further though they talked at least another ten minutes.

It’s hard to ignore that there are places all over town where the h’s name (Herb) is spray painted on a wall. Never mind that the spray painter is expressing a love for weed; it’s disconcerting to see the h’s name writ large on the way to the store, out walking Jake, or on the wall bordering the Queen’s land, like a greeting everywhere we go.

One thing the place attachment guru recommends that I have ignored is the edict to create a third place for yourself - not work, not home but somewhere else. I have worked at home since 2008, and though I never say never, I feel pretty comfortable saying I’ll never go back to an office-y office. My home has always been more than just a place to lay my head or work my butt off - it is my refuge from the world, a palace of books and dogs and art and plants where I can hide from or venture forth into the world, depending on my mood. Before I got a dog and had to walk him twice a day, I would sometimes spend days on end inside my kingdom, only going out if I ran out of some essential like food or toilet paper. And this home, here in Portugal, is like a culmination of all the good things I’ve ever liked about every home I’ve ever had, as though my whole life has been practice for this moment.

Do you think this place is haunted, I asked the h when we’d been here for a week.

Yes, he said promptly. Then he clarified; It’s like your ghost was already here, and we’ve just joined it.

I know what he means, I kind of thought the same thing when I saw the tiles mounted on the front of our house on either side of the front door. On one side it says "My house is my world”, which has always been a private personal motto of mine. I love to travel, especially to visit friends, but I’d just as soon stay put and have my world of friends come to see me.

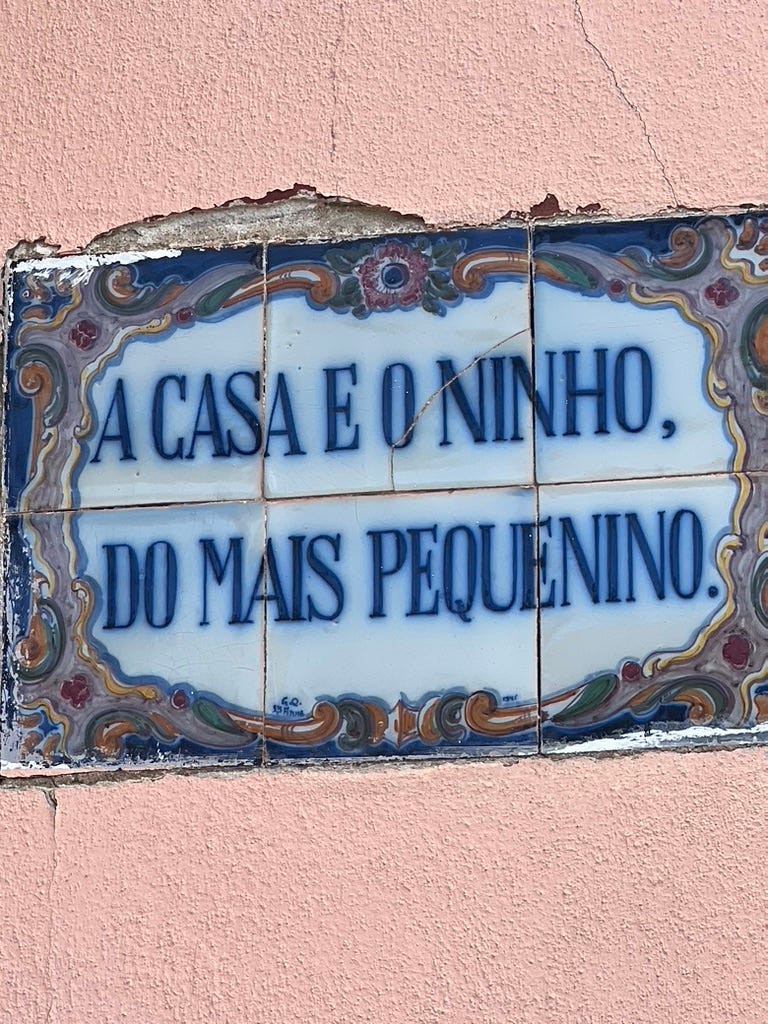

On the other side of the door the tiles read “The home and nest of the little one”. That was my nickname in college - Little One. I was a fastpitch pitcher on a softball team that went all the way to the College World Series my freshman year. At 5’3” and 100 lbs I was the smallest player on the team, and quite possibly in the entire NCAA, and the nickname was so ubiquitous that at one point the umpire checking over the lineup before the game remarked, Hey you guys forgot to list Little One. I had to tell him, that’s not actually my name, you know.

Maybe it’s all just a big coincidence, seeing our names on our new home and buildings all around us, but it gives us a beautiful sense of place attachment like nothing else.

Such a beautiful and inspiring essay. Do you bottle your resilience for sale? One please.